Gaudete and The Reverend Lumb’s Parish and Parishioners.

First published in the Ted Hughes Society Journal, Vol 4, 2014.

© Ann Skea.

One of the most striking things about Gaudete is the intense sensory impact it makes on the reader. This is not just the result of the dark, disturbing violence of some of the scenes or of the strong erotic and sexual energies which are present throughout. The effect of both of these is amplified by the underlying suggestion of occult rituals and demonic possession and, more subtly, by the way in which Hughes immerses us in the sounds, the smells, the disorientation of pain, the heat of animal bodies, the feel and the cling of blood, mud and water and the sheer abundance of plant and animal life in the Springtime landscape.

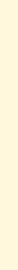

Amongst this sensory richness, the visual element is so strong that Hughes appears to describe the changeling Lumb and his parishioners as if he had a clear and distinct vision of each of them inside his head. Each person is evoked through an accumulation of small details embedded in the poem: we learn what they look like, what their home looks like, what car they drive; and their actions and feelings consistently reflect their personality. Similarly, the landscape in which the drama takes place has a logical and consistent shape, and small details suggest that Hughes had a clear map of it in which to set the ‘headlong narrative’ through which he wished to push his readers1.

Major Hagen is the character most clearly pictured, perhaps because Hughes originally intended him to be central to the story2. Hagen is a retired army man who breeds beef cattle and keeps a stud stallion. At different times, we see him checking sperm counts and supervising the mating of a stallion and mare. We also see him striding along his chestnut–tree–lined drive in his ‘cleated boots’ and his tweeds, with his beloved double barrelled Purdey clutched under his arm. We are shown the ‘nicotine–yellow–dullness’ of his eyes; the ‘exemplary scraped steel hair’ on his ‘bleak skull’; and the ‘ginger–haired, freckle–backed thick fingers’ with which he focuses his binoculars as if in a game-hunting machan.

Inside Hagen’s ‘squat elegant residence’ there is his glass-fronted gun cupboard, his butterfly collection and a hunt–souvenir tiger skull used as a paperweight on his desk. There are parquet floors, cut–glass doorknobs, and magenta tiles and a blue Aga in the kitchen. It is an interior which his thirty–five–years-old wife, Pauline, with her ‘nerve-harrowed face’ and stylish clothes, sees as ‘barren perspectives/ Cluttered with artefacts,[…]/…Icebergs of taste’.

Inside Hagen’s ‘squat elegant residence’ there is his glass-fronted gun cupboard, his butterfly collection and a hunt–souvenir tiger skull used as a paperweight on his desk. There are parquet floors, cut–glass doorknobs, and magenta tiles and a blue Aga in the kitchen. It is an interior which his thirty–five–years-old wife, Pauline, with her ‘nerve-harrowed face’ and stylish clothes, sees as ‘barren perspectives/ Cluttered with artefacts,[…]/…Icebergs of taste’.

‘Anaesthetised/ For ultimate cancellations’ by his military career, Hagen shoots birds with cold, military efficiency, and taunts his wife and the Reverend Lumb with a bloody carcass. When roused, however, his crimson–faced anger is violent and uncontrolled. His deadly reaction to danger is displayed when his dog attacks him and he kills it. And his sudden baffled horror when he realises what he has done suggests dismay at his own loss of control, as well as regret for the loss of a loyal dog.

Hagen, alone of all the village men who have been cuckolded, refuses to be part of the disorganised pursuit of Lumb across the fields. Instead, he waits and, like the game–hunter he once was, he watches Lumb jig ‘like a puppet’ in the ‘ten magnifications’ of his telescope until he reaches the lake on Hagen’s own land. There, united with ‘his first love’ the Mannlicher ·318, Hagen shoots Lumb in the head from the window of his truck.

All the characters in Gaudete are similarly described through the accumulation of small details embedded in the poem. Far from developing Gaudete as a money-making film–script, as he once planned3, Hughes’ ultimately created clear and vivid evocations of people and place which need no film for us to be able to see them. He adopted, he said in a letter to Terry Gifford and Neil Roberts, an ‘‘acting out’ style of story–telling’, which stirred the senses and ‘liberated’ his images into ‘imaginative freedom’ rather than entangling them with an ‘intellectual response’4. True, his characters tend towards stereotypes and their actions are, as Hughes said, ‘slightly puppet like’5. Feminists have complained about Hughes’ narrow presentation of the women in the story, but the men are equally one–sided. Yet, it is this one–sidedness, this cartoon–like quality, which adds to the clarity with which we see them in our own imaginations and which allows us to experience the dramatic speed and energy of the poem.

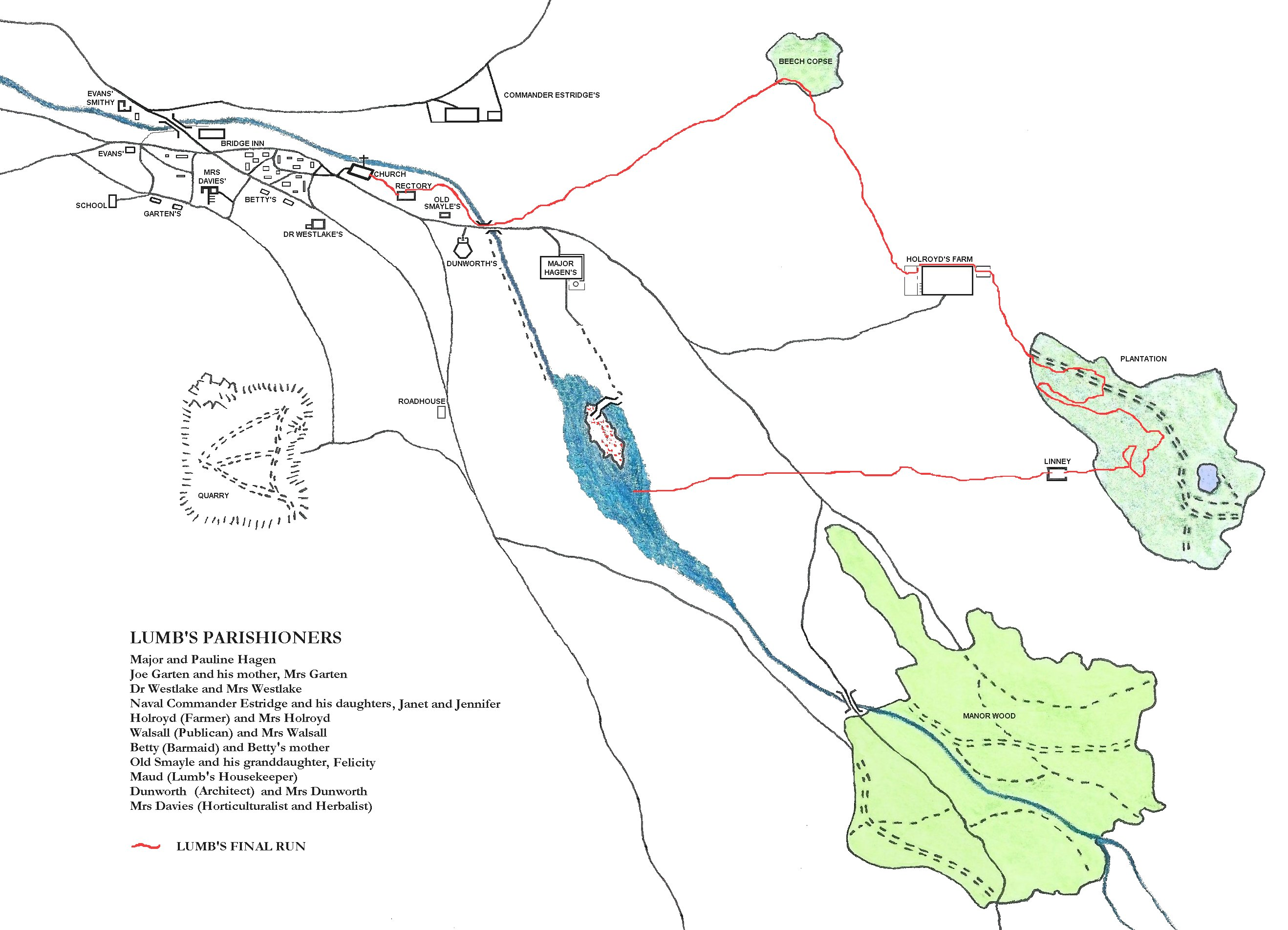

In the same way, accumulated topographical details allow us to build an imaginary map within which to visualize the action. Commander Estridge, for example, can see through his telescope, the village; men cutting beech trees three fields beyond Holroyd’s farm; and the door of the farm’s barn. Joe Garten, cycling home from his poaching in the woods, admires the river and then notes the Reverend Lumb’s blue van in the entrance to the quarry. And Betty, who has met Lumb at the quarry, has cycled there from the Bridge Inn during her lunch hour. From information such as this, I developed my own imaginary map and my attempt to draw it can be seen below. I am not suggesting that this is the map Hughes had in his head, only that the visual element of the sensory immersion I experienced as I read the poem was vivid enough for me to place clearly imagined characters in a definite and realistic landscape.

1. Faas, E. ‘Appendix II’, The Unaccommodated Universe, Black Sparrow Press, Santa Barbara, 1980. p.214.

2. Faas, op.cit. p.215.

3. Letter to Keith Sagar, Reid, C. (Ed.), Letters of Ted Hughes, Faber, 2007, pp.383-5.

4. Letter to Terry Gifford and Neil Roberts, Letters of Ted Hughes, p.428.

5. Ibid.

Inside Hagen’s ‘squat elegant residence’ there is his glass-fronted gun cupboard, his butterfly collection and a hunt–souvenir tiger skull used as a paperweight on his desk. There are parquet floors, cut–glass doorknobs, and magenta tiles and a blue Aga in the kitchen. It is an interior which his thirty–five–years-old wife, Pauline, with her ‘nerve-harrowed face’ and stylish clothes, sees as ‘barren perspectives/ Cluttered with artefacts,[…]/…Icebergs of taste’.

Inside Hagen’s ‘squat elegant residence’ there is his glass-fronted gun cupboard, his butterfly collection and a hunt–souvenir tiger skull used as a paperweight on his desk. There are parquet floors, cut–glass doorknobs, and magenta tiles and a blue Aga in the kitchen. It is an interior which his thirty–five–years-old wife, Pauline, with her ‘nerve-harrowed face’ and stylish clothes, sees as ‘barren perspectives/ Cluttered with artefacts,[…]/…Icebergs of taste’.